People have been raving about SRS (Spaced Repetition Systems) as a tool for language learning for ages. The gist is that, by spacing out flashcards for vocab, repeating the cards you get wrong more frequently, and the ones you get right exponentially less frequently, you can solidify that knowledge in your meat hard-disk.

If SRS is the goat of vocab acquisition, then Anki is the goat of SRS systems. The only issue being, to be able to use an SRS system, you need to have flashcards to review. And while solutions for clipping text, movies, etc. exist, this doesn’t fit the way I acquire vocab, which is through oral conversations, from class and other materials.

I need a way in which I can take words I learn on the fly, input them in, and have a translated and formatted flashcard sitting in my SRS ready for review.

I use Obsidian btw, and this comes in handy for tackling this problem. Being built with a “file over app” approach, means I can just use standard file manipulation techniques to fill my vocab list, and let iCloud handle the syncing across my devices. Pair this with the YAML front matter support, and Templater as a way to template my flashcards and run CommonJS scripts, and we’ve got ourselves a workflow that supports vocab ingestion, categorisation and search.

The setup

Get these tools:

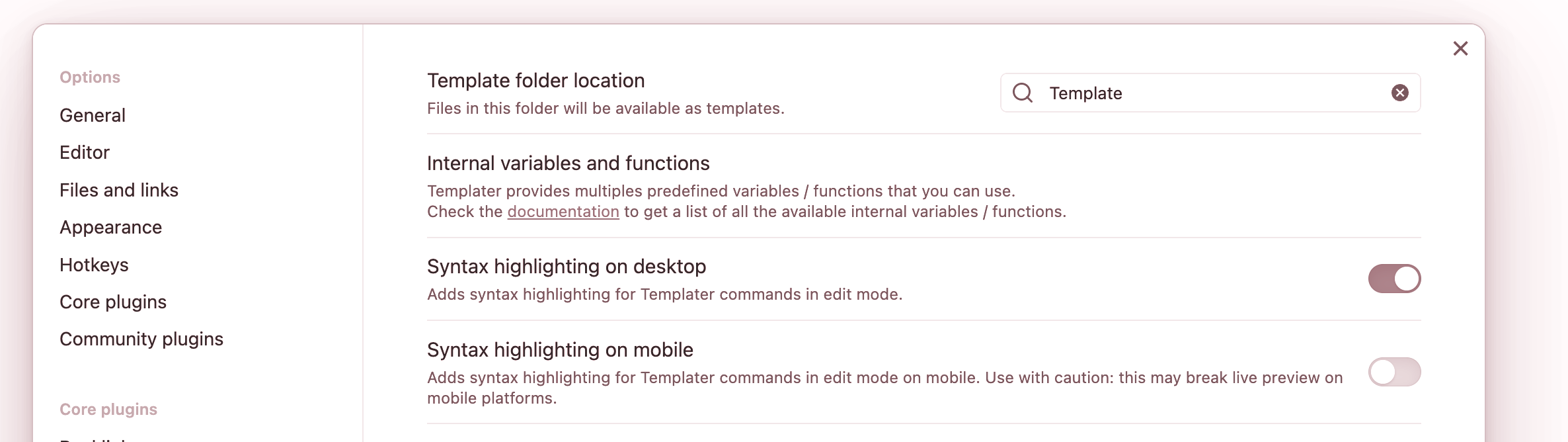

The idea of Templater is to give your Obsidian workspace a templating language that also allows you to automate file creation and other tasks.

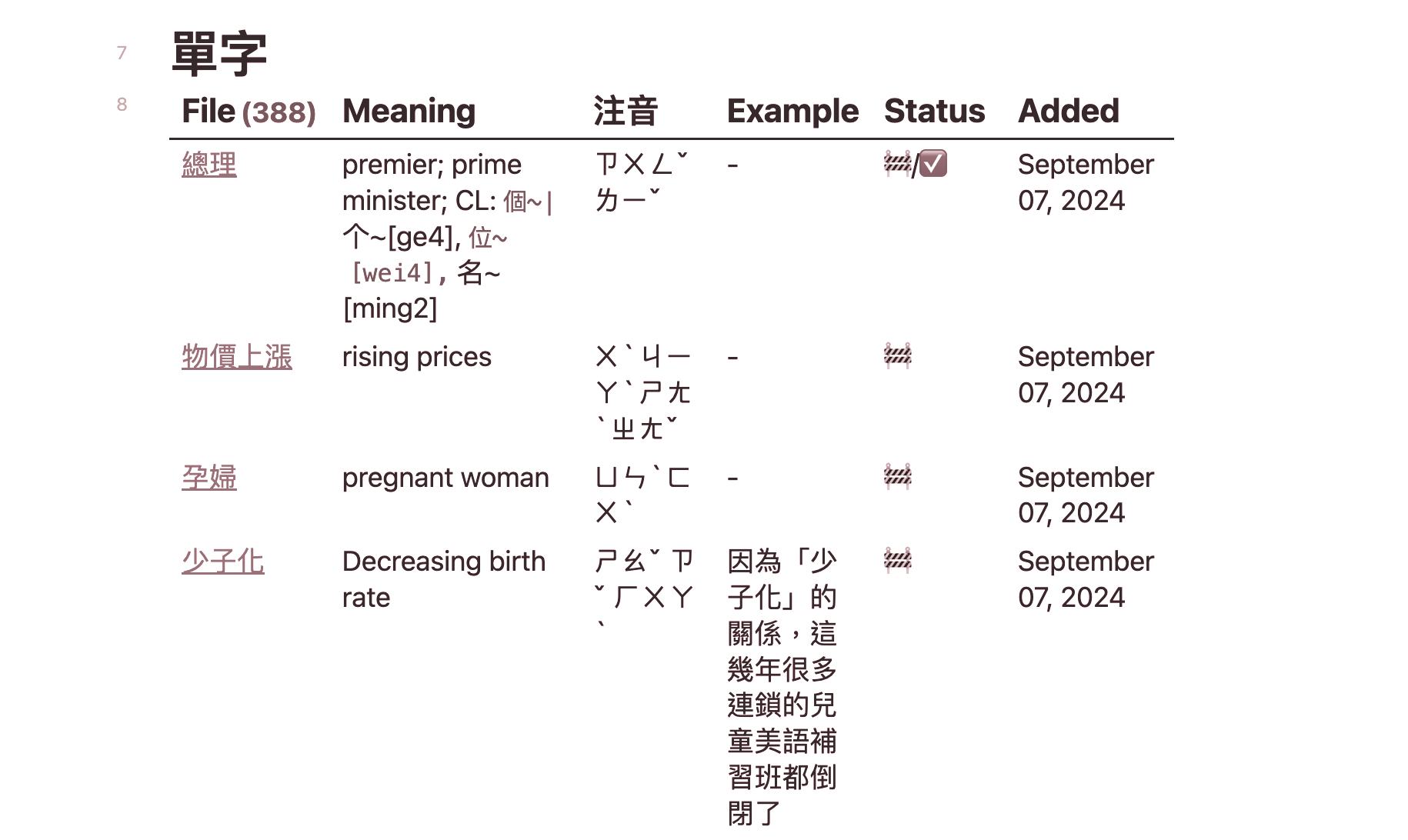

Let’s start by creating a Template/ folder where all of our Templater templates will live. Let’s set that folder as the place Templater should look for these templates.

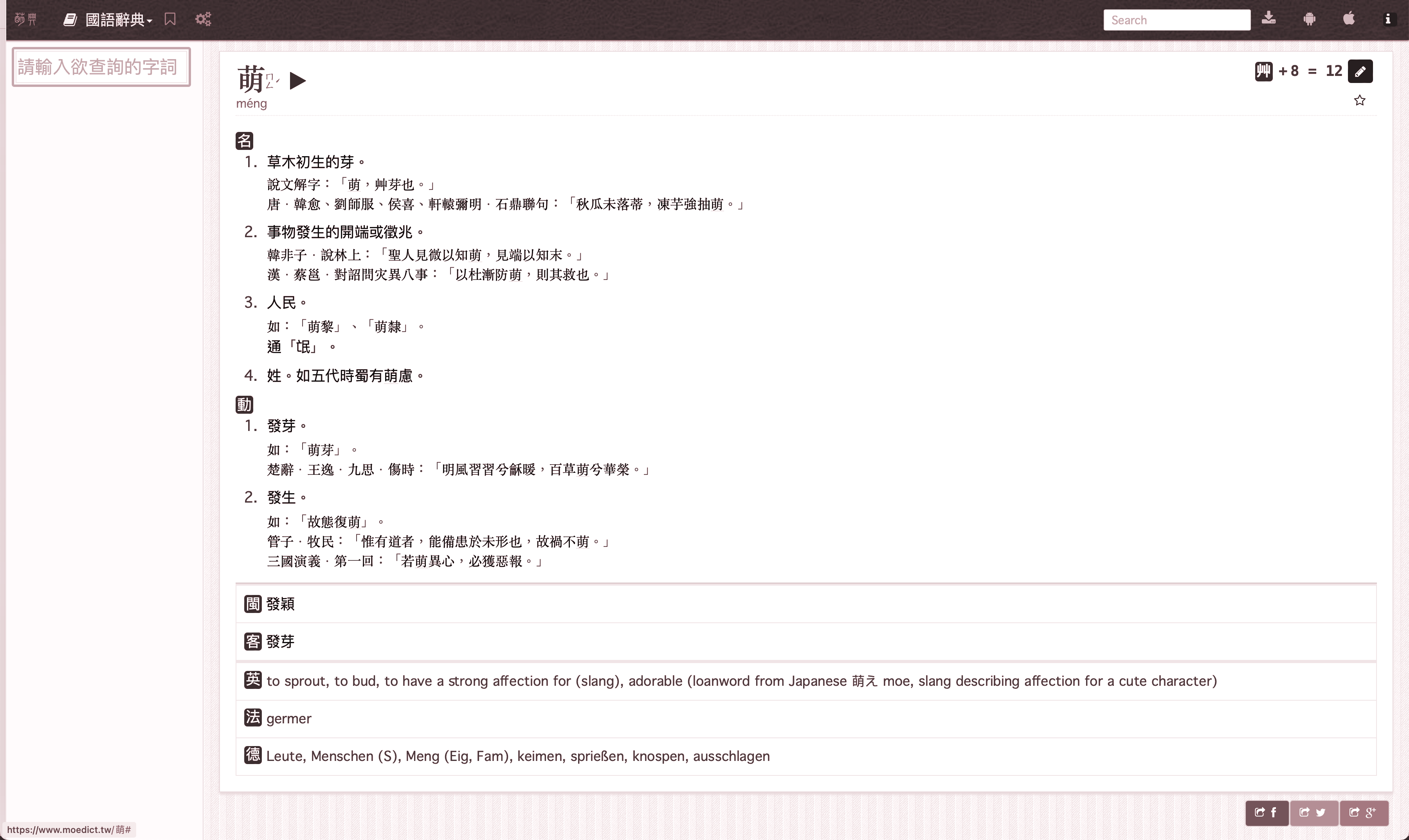

Now for our first template, let’s create a file under Template/, and fill it as such:

---

hanzi: <% tp.file.title %>

meaning: <% tp.user.translation(tp.file.title) %>

zhuyin: <% tp.user.bopomofo(tp.file.title) %>

example: <% tp.user.example(tp.file.title) %>

status: 🚧/✅

added: <% tp.date.now("YYYY-MM-DD") %>

---

#中文

## <% tp.file.title %> #card/reverse

<% await tp.user.translation(tp.file.title) %>

<% await tp.user.bopomofo(tp.file.title) %>

## 例子

<% await tp.user.example(tp.file.title) %>

<% tp.file.move("華語/單字/" + tp.file.title) %>

There’s a lot going on here, but let’s break it down:

---: Whatever’s encoded between these lines is front matter, a schema for adding metadata to YAML files<% %>- enclosed Templater directives- tags the file with #中文 for organisation

- tags a paragraph with

#card/reverse, which tells the Flashcard plugin that the following paragraph is a card, and you should create a double-sided card (so we can practice ZH -> EN and EN -> ZH)

When we execute this template, Templater does the following:

- hydrates the template with the file title

- calls user-defined functions

translation,bopomofoandexample - moves our file to a separate folder where all the vocab lives

With Templater’s hooks, you can execute a sync operation so that the card is automatically synced with Anki, but I dislike doing this doesn’t work on iPad

You might’ve noticed that we’re calling some user-defined functions, such as tp.user.bopomofo. Templater allows you to define CommonJS scripts that can be run when a template executes, or hook into other Obsidian or Templater commands.

We’re going to use Template/Scripts/ as our JS scripts folder.

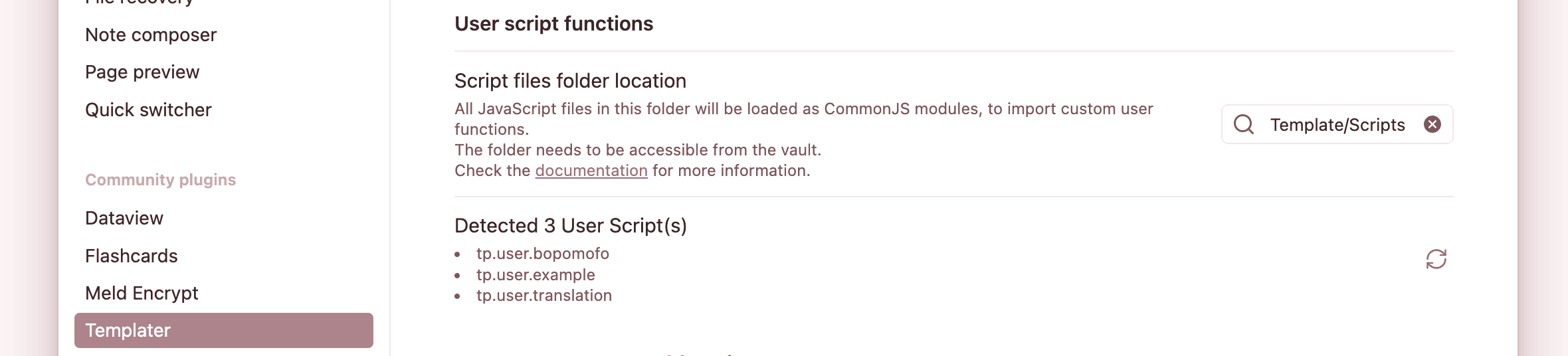

Moedict, the community’s Mandarin, Hokkien and Hakka dictionary

g0v.tw is a grassroots, decentralised, civic tech community founded in Taiwan. It has many contributors, including Taiwan’s former Minister of Digital Affairs, Audrey Tang, and has contributed many open source projects.

One of these, is moedict.tw, a snappy, community-driven Mandarin, Hokkien and Hakka dictionary, which is easily queryable through an API interface.

We can query loads of information about a word, from translation, to zhuyin representation, to even stroke number and radical composition:

≫ curl "https://www.moedict.tw/a/總理.json" | jq .

{

"Deutsch": "Kanzler (S)",

"English": "premier",

"francais": "premier ministre",

"h": [

{

"=": "541700009",

"b": "ㄗㄨㄥˇ ㄌㄧˇ",

"d": [

{

"f": "`總管~`掌理~。",

"q": [

"`清~.`崑岡~《`大清會典~`事例~.`卷~`一~`八~`一~.`戶部~.`庫藏~》:「`雍正~`元年~,`特命~`王公~`大臣~`總理~`三~`庫~,`鑄~`給~`印信~。」"

]

},

{

"f": "`國父~`孫中山~`先生~`創立~`的~`同盟會~,`及~`後來~`改組~`的~`中華~`革命~`黨~、`中國~`國民~`黨~`時期~,`都~`被~`推舉~`為~`總理~。`逝世~`後~`永存~`此~`名~,`成~`為~`黨員~`對~`他~`的~`專~`稱~`與~`尊稱~。"

},

{

"f": "`內閣制~`國家~`的~`行政~`首長~。",

"l": [

"`也~`稱~`為~「`內閣總理~」。"

]

}

],

"p": "zǒng lǐ"

}

],

"t": "`總~`理~",

"translation": {

"Deutsch": [

"Kanzler (S)",

"Ministerpräsident (S)",

"Premierminister (S)"

],

"English": [

"premier",

"prime minister",

"CL:`個~|`个~[ge4],`位~[wei4],`名~[ming2]"

],

"francais": [

"premier ministre"

]

}

}

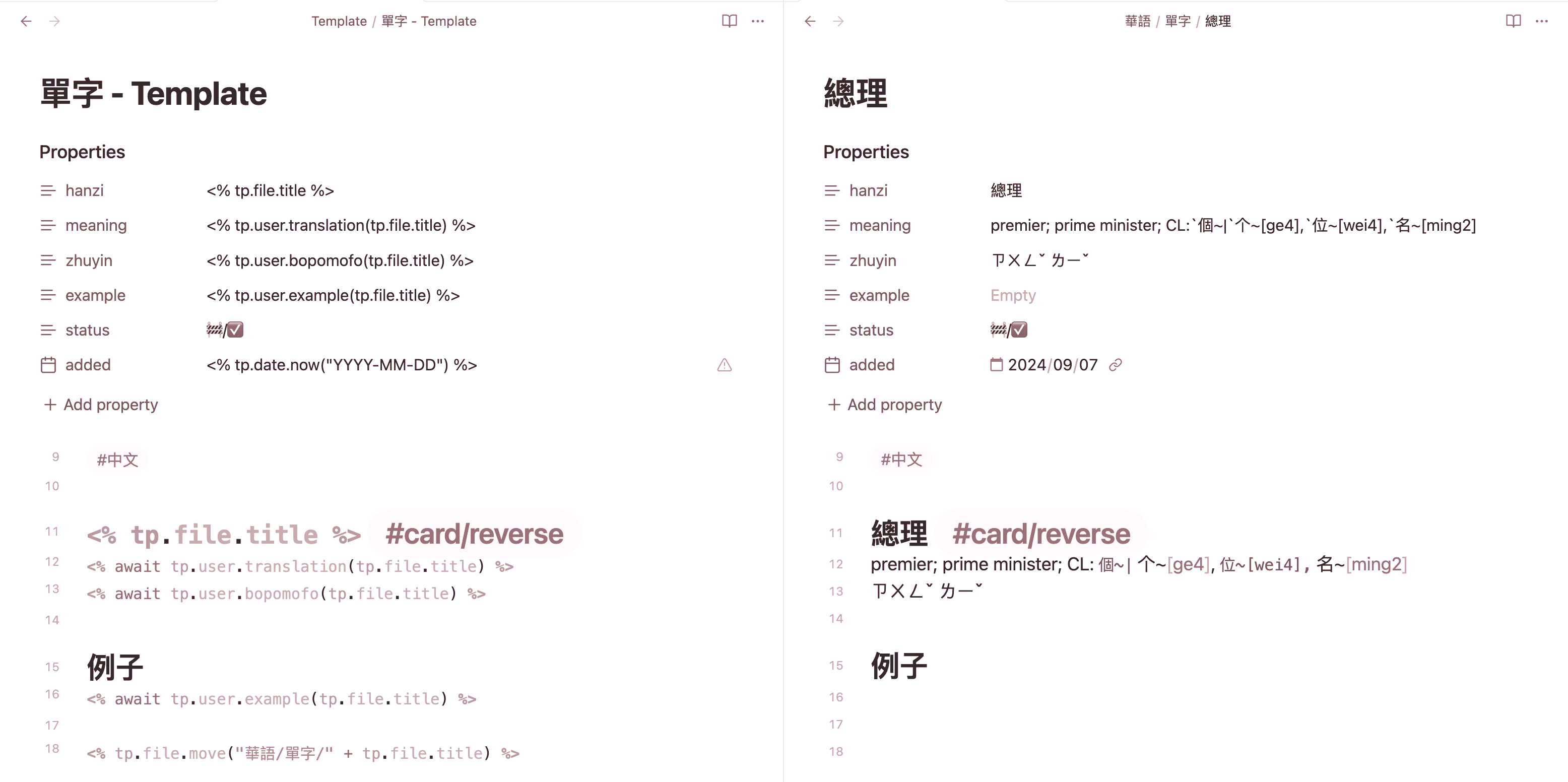

We can use this data in our user-defined functions, for example, we can extract the translation:

async function translate(text) {

try {

const response = await fetch(`https://www.moedict.tw/a/${text}.json`);

const translationBody = await response.json();

let translation = translationBody.translation?.English;

if (translation) {

translation = translation.join("; ");

} else {

translation = translationBody.English || translationBody.english || "";

}

return translation;

} catch (e) {

return "MEANING";

}

}

module.exports = translate;

With this function defined, we can call it from Templater as such…

<% await tp.user.translation(tp.file.title) %>

… and get this result

Dataview: a way to query your front matter-rich vocab

In my practice workflow, I often want to see a huge list of vocab I’ve learned over time, so that if, say, I have to write an article piece as my homework, I can quickly scan all the vocab I’ve learned and use it in practice.

Here’s where Dataview comes in, an Obsidian plugin that allows you to write SQL-like statements to query your Obsidian files based on tags, folder location, and most importantly, front matter.

I create a 華語/Data Index.md file where I keep all my Dataview scripts

We can use the front matter metadata we created earlier as the columns in our Dataview table:

TABLE

meaning as "Meaning",

zhuyin as "注音",

example as "Example",

status as "Status",

added as "Added"

FROM "華語/單字"

And that’s about it, from here the sky is really the limit to what you can do with this workflow, some ideas could well be:

pipe the

exampleoutput to ElevenLabs or another TTS program to get an audio file to include with your flashcard to train your listening skillscreate a tingxie workflow where you pull down the examples, run them through TTS and test yourself in how well you can write down the characters the TTS just enunciated

I may very well attempt some of these in the future, and will report back with the results.